Anthony Fauci Behind Covid Origins Disinformation, Evidence Suggests

Communications between scientists show pressure from “higher ups” to dismiss the lab leak theory of Covid origins

Last week Public and Racket revealed that top researchers privately believed a lab leak was plausible despite claiming to rule it out in a hugely influential March 2020 paper, “The Proximal Origin of SARS-CoV-2.” These revelations have led to growing calls by neutral observers for Nature Medicine to retract the paper.

“I’m not a big petition guy,” said statistician Nate Silver, “but if Nature isn't ready to retract this paper on their own that's a big L for their credibility and about as clear a sign as you can get that they're elevating politics above science.”

Roger Pielke, Jr., a leading science policy expert, wrote, “The case for retracting Proximal Origins is overwhelming because we now know, undeniably, that it was seriously flawed and misleading.”

Yet on July 22, Nature Medicine’s editor-in-chief, Joao Monteiro, told The Telegraph that a retraction was “not warranted” because the paper was a “point of view” and not a research study.

In 2020, however, Nature Medicine and the paper’s authors presented “Proximal Origin” as a peer-reviewed analysis, not as an opinion piece. Then-director of the National Institute of Allergies and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), Anthony Fauci, upheld the paper as definitive scientific research, and the World Health Organization (WHO) used it as a basis for ruling out “deliberate bioengineering” in its own origins investigation.

It appears that Nature Medicine is framing this paper as a “point of view” because the authors’ private Slack messages show that they had major misgivings about their own evidence and findings.

The question now turns to why the scientists decided to rule out “any laboratory-based scenario” despite privately recognizing that such a scenario was, indeed, highly plausible.

As Public documented, the process of writing “Proximal Origin” was a scramble for intermediate species — first, ferrets, and then pangolins — to explain how the virus could have jumped from bats to humans.

And even then, the scientists did not fully believe their own explanation. In April 2020, two months after the pre-print of “Proximal Origin,” Kristian Andersen and the other authors still had doubts about the zoonotic spillover hypothesis.

The authors now claim that their decision to mislead the public and conceal information was simply “scientists doing science,” but the discrepancy between their public and private statements is simply too large to justify.

Good scientists frequently make painstaking observations before they can come to conclusions. Data must be collected, often multiple times. Analyses must be conducted and re-conducted to ensure that the findings are sound.

There are good reasons for such patience. Science has for years been in what is known as a “replication crisis.” Efforts to replicate the findings of even famous studies have repeatedly failed, in multiple disciplines. And the cost to scientists’ reputations and careers of rushing to judgment is high, as the recent demands for the retraction of “Proximal Origin” show.

So why, then, did the “Proximal Origin” scientists risk their reputations by pushing forward with a poorly-reasoned paper? For their three months of discussion, the authors were keenly aware of the political implications of a lab leak. If anyone accused China of releasing the virus, it would be a “shit show,” Andrew Rambaut of the University of Edinburgh said.

But political concerns alone do not explain the authors’ decision to publish. They knew that completely discounting a “laboratory-based scenario” was unwise and that they lacked sufficient evidence to do so.

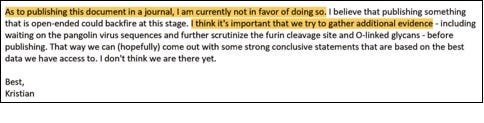

“As to publishing this document in a journal, I am currently not in favor of doing so. I believe publishing something that is open-ended could backfire at this state,” Andersen wrote on February 8, 2020. “I think it’s important that we try to gather additional evidence — including waiting on the pangolin viral sequences and further scrutinize the furin cleave site and O-linked glycans — before publishing.”

We know though, that the group never did find conclusive pangolin sequences. “Unfortunately the pangolins don’t help clarify the story,” Andersen wrote on February 20, three days after the authors published their pre-print.

If Andersen didn’t get the evidence he said was needed, why did he publish?

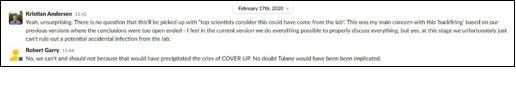

The authors were also aware of the fact that misrepresenting the data would be unethical. On February 9, Robert Garry of Tulane University argued that not addressing accidental infection in a lab would look “like a cover up.” And again, on February 17, Garry asserted that ruling out accidental release would lead to “cries of COVER-UP.”

So why did the “Proximal Origin” scientists end up jeopardizing their status and esteem by rushing to publish a paper they knew was misleading? And who ultimately pushed them to engage in this cover-up?

“Pressure From On High”