Why Environmentalists May Make This Whale Species Extinct

On the 50th Anniversary of the Endangered Species Act, green groups throw their once-sacred "precautionary principle" to the wind.

Since the passage of the 1973 Endangered Species Act, environmentalists have fought for strict protections for endangered species. They have demanded that the government apply what is known as the “precautionary principle,” which states that if there is any risk that a human activity will make a species extinct, it should be illegal.

And yet here we are, on the 50th anniversary of the Endangered Species Act, watching the whole of the environmental movement — from the Audubon Society and the National Wildlife Federation to scientific groups like the Woods Hole Institute, New England Aquarium, and Mystic Aquarium — betray the precautionary principle by risking the extinction of the North Atlantic right whale.

The cause of this environmental betrayal is massive industrial wind energy projects off the East Coast of the U.S. The wind turbine blades are the length of a football field. Sitting atop giant poles they will reach three times higher than the Statue of Liberty. The towers will be directly inside critical ocean habitat for the North Atlantic right whale.

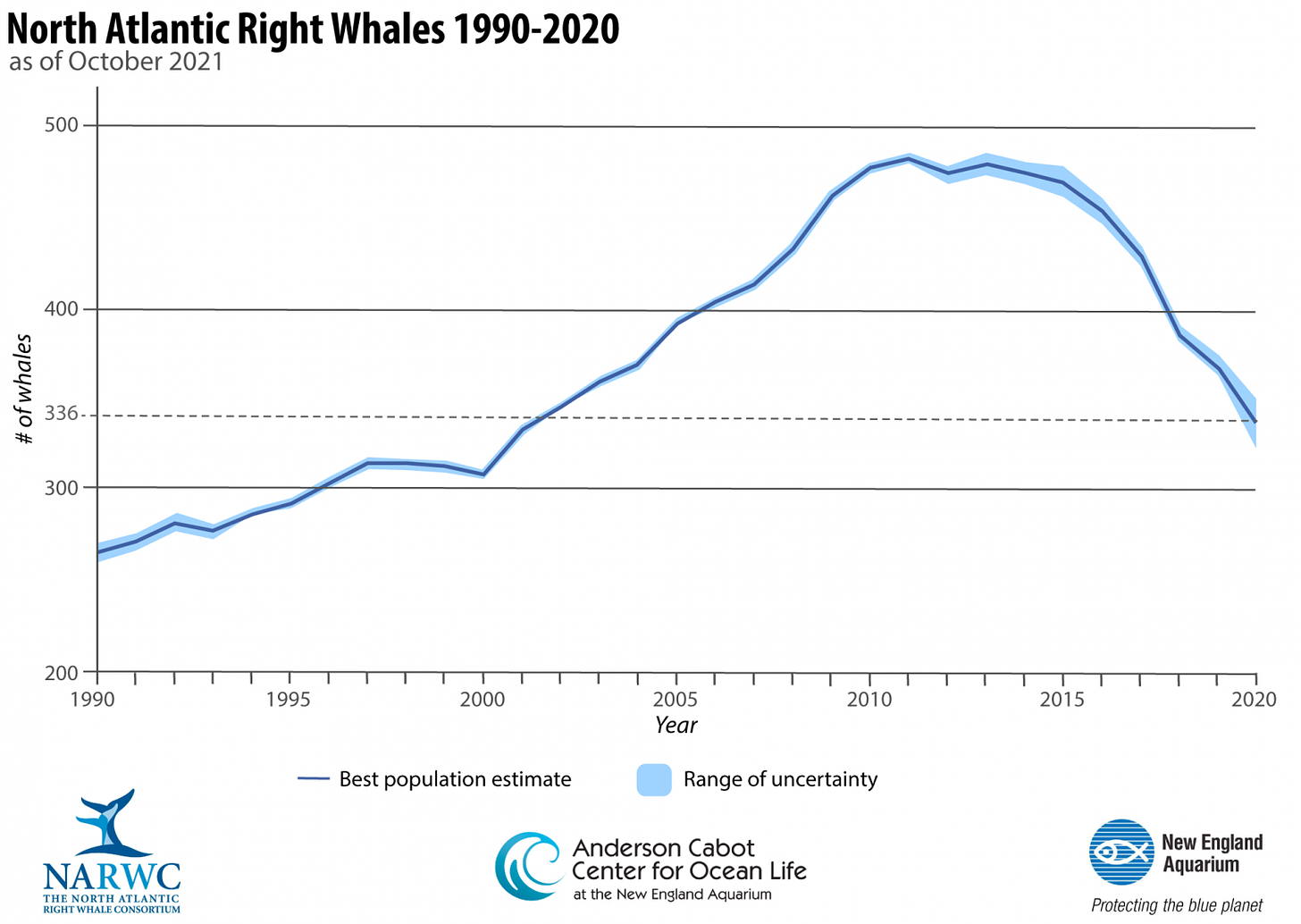

There are only 340 of the whales left, down from 348 just one year earlier. So many North Atlantic right whales are killed by man-made factors that there have been no documented cases of any of them dying of natural causes in decades. Their average life expectancy has declined from a century to 45 years. A single additional unnatural and unnecessary death could risk the loss of the entire species.

Surveying for, building, and operating industrial wind projects could harm or kill whales, according to the U.S. government’s own science.

The National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) has given the wind industry 11 “incidental harassment authorizations,” or permits to harass hundreds of whales, including 169 critically endangered right whales.

The industry will bring more ships into the areas that could strike and kill whales. Submarine noise pollution from the wind farm’s construction and operation, and entanglements in equipment, also add to the risk. So too could air turbulence generated by the turbines harm or destroy zooplakton feeding grounds.

And, now, wind developers are demanding higher speed limits for their boats. If they don’t get them, the industry claims, it will need to build hotels for the workers at the sites, right in the middle of right whale habitat.

Defenders of the wind projects say they can reduce and mitigate the noise and ship traffic from the wind farm construction, but a senior scientist with the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) contradicted that claim last spring when he wrote in a letter that “oceanographic impacts from installed and operating [wind] turbines cannot be mitigated for the 30-year lifespan of the project unless they are decommissioned.”

Scientists representing many of the same environmental groups supporting the industrial wind energy projects wrote in a 2021 letter that “the North Atlantic right whale population cannot withstand any additional stressors; any potential interruption of foraging behavior may lead to population-level effects and is of critical concern.”

Industrial wind projects “could have population-level effects on an already endangered and stressed species,” concluded the NOAA scientist, Sean Hayes. What are “population-level effects?” In a word: extinction.

What is going on? How is it that nearly every major conservation and environmental organization is actively championing industrial energy projects that could lead to the extinction of a whale species?